Any discussion of irrigation in Florida begins and ends with two things – the reserves that supply the water and the "water cycle" via which that water is recycled and reused many times over.

Understanding the ultimate sources of the water upon which Floridians rely for irrigation purposes helps to develop a clear focus on using that water in the most sustainable manner possible. We’ve previously considered whether it's possible to both irrigate effectively and responsibly. We've also looked at how irrigation systems for today and the future must enable sustainable irrigation practices. In this article we’ll look at the water itself, at where it comes from and where and how it returns to source, and at the steps above and beyond the mechanics of an irrigation system that people can take to protect and preserve this most precious of resources.

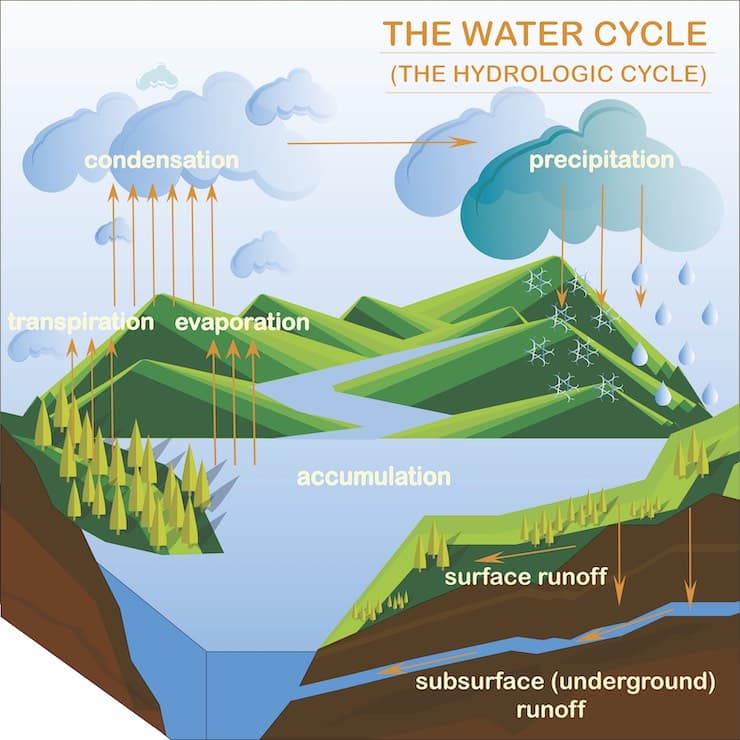

Given that more than 50% of the water used in Florida is used for irrigation purposes, and that the climatic trend is clearly pointing toward declining levels of rainfall (difficult though this may be for anyone caught in a hurricane-driven downpour to believe), it is more important than it’s ever been for decisions regarding irrigation to be based on a firm grasp of the basic of water supply. The water cycle illustrated below shows how water in our environment is naturally 'recycled' both on, above and below the earth. But human activities from agriculture and industry to urbanization also contributes to and alters the water cycle.

The water used in Florida, ultimately, derives from vast underground reserves of freshwater known as aquifers. These aquifers feed large amounts of freshwater to sources such as lakes, springs, streams and wells, which are then utilized to supply irrigation systems. The vast bulk of the aquifers in Florida are located hundreds of feet beneath the ground, covered with sediment and impermeable material which prevents the water moving upward across the majority of the aquifers. The exceptions to this restriction of upward movement take the form of small openings which create more than 1,000 springs across the state. More than 30 of these springs have an average flow rate of more than 100 cubic feet per second, which equates to 64.6 million gallons per day. Any increase in the amount of water being withdrawn from streams and lakes reduces the flow of water in these springs, impacting on their effectiveness as a source of water supply. For this reason alone, irrigation systems which draw from lakes and streams have to be designed to operate efficiently on the minimum possible amount of water in order to keep the springs functioning to maximum effect.

A noticeable feature of many urban developments in Florida are the man-made lakes and artificial canals. When it comes to lakes, it seems almost impossible to find a community that isn’t without one or more, and they serve a very important function when it comes to irrigation. Many are put in place to hold stormwater run-off or treated water that's then re-used for irrigation. These need to be managed effectively and have proved one of the most important mainstays of landscape irrigation. In other words they both make use of, and contribute to, the water cycle.

Another aspect of the operation of the water cycle in Florida that has to be taken into account is the problem of the intrusion of saltwater into the freshwater aquifers. The geographical realities of Florida – as a peninsula located between two saltwater bodies - means that saltwater is constantly pressing to enter and corrupt the aquifers. While the freshwater levels in the aquifers are above sea level the pressure within the aquifer is sufficient to stop the saltwater travelling inland and entering the aquifers from below. During periods of drought or dryer weather, however, the pressure of the freshwater drops as it is not replenished by rainfall. When this happens, saltwater is able to intrude into the aquifers and corrupt the quality of the water.

One more factor which impacts on the quality of the water available – in this case in rivers, streams, canals and lakes – is runoff. Runoff refers to water which, instead of recharging the aquifers via the ground, flows directly into other bodies of water. An increase in the use of impermeable surfaces in commercial and residential settings – in places such as roads, car parks, driveways and the buildings themselves – can have the twin impact of reducing the amount of rainwater able to directly replenish the aquifers while increasing the amount which runs off and into other bodies of water. Runoff water of this kind is likely to be tainted with a range of pollutants, however, which will then impact on the quality of the bodies of water involved. Careful planning of public and private spaces is needed to minimize runoff, while careful management of the landscaping of these spaces and the materials used to maintain that landscaping can play a vital part in improving the water quality of any runoff which is present.

The delicate balance which governs the supply of water across Florida and the quality of that water is reflected in the water cycle, which, in its most basic iteration, consists of evaporation, condensation and precipitation.

The role that residential or commercial irrigation planning plays in this cycle is hard to overstate, particularly when the impact of each property is extrapolated on a state-wide basis. In simple terms, every drop of water that falls onto a particular area of land will either permeate the ground to enter the local aquifer or evaporate away to eventually fall again as rain. The exception is the water which takes the form of runoff, and this can be generated in two ways.

The first and most obvious source of runoff water is the water that runs off non-permeable surfaces of hard landscaping features like pavements, roads and pathways and buildings. The second, less easily seen, source of runoff water comes from over-watering and/or ill-directed watering - generally from poorly managed and maintained irrigation. Put simply, the soil in any given area – depending upon factors such as the time of the year and the climatic conditions – is only ever able to absorb a certain amount of water. If the water applied to this area via irrigation is more than this set amount then a percentage will simply sit on the surface and eventually evaporate or, if any slope is present, run off until it meets the nearest body of water. Just as wasteful, irrigation that never quite reaches the root level (whether because it's not enough, or it's applied in the wrong places) brings its own issues, for example, gathering in quantity on the hardened earth - and creating runoff. And of course everyone in the business knows - water waste isn't only bad practice but it's bad for your reputation and will increase the cost of running irrigation.

Either way, this presents anyone responsible for landscaping and irrigation management with a challenge: To irrigate in such a way that the water being applied is only ever as much as that landscape needs at any given time - and ensuring zero water waste. To do that, you need as much control over the system as possible, 24/7. Here at Hoover, our answer is a total irrigation solution. Our irrigation systems are designed and installed using a fully integrated approach of a properly adjusted and well-designed system set up - VFDs, points of connection, optimum pump pressures and horse power - along with smart technology that uses real time data from external factors like the weather – to help ensure that the irrigation is delivered with maximum efficiency and minimum waste.

Given that some runoff is always going to occur, however, there are still steps which individuals can take over and above the application of smart irrigation systems in order to ensure that any unavoidable runoff has only a minimal impact on the bodies of water affected. These include disposing of any pet waste, only using fertilizers if needed and when plants are actively growing, sweeping waste such as grass clippings and excess fertilizer off any paved areas and planting vegetation which is most likely to thrive with the minimum of irrigation and fertilization. Other positive interventions include the use of mulch to retain soil moisture, landscaping which features rises and dips (known respectively as berms and dales) to encourage water retention, and features such as paths and patios constructed using permeable materials.

It’s easy to take our landscaping for granted, but any consideration of the water cycle reveals a finely balanced mechanism that must be protected, particularly during an era of declining levels of precipitation. Clearly thought-out landscaping and a well-designed, installed and maintained irrigation system combine to offer that protection and make sure that all water requirements are met in the future.